By Miles Flynn | Southern Indiana Business Report

PAOLI — The farm-to-table program at Paoli Junior-Senior High School is helping teach lifelong lessons for local students while also blazing a trail for ag education in the Hoosier State. With a goal of engaging pupils in more hands-on learning and problem solving, the student-run business is now in its seventh year of raising pork and lettuce on campus to sell to the school system’s cafeterias and to the community via Lost River Market & Deli and other avenues.

Students oversee operations

“We run it just like a real business,” said Cory Scott. He and Kyle Woolston handle duties as ag teachers for Paoli students in grades 7-12.

Students are integral in all processes, beginning with breeding and raising the animals. The whole operation started with a gilt named Boots who was housed in a converted greenhouse off the rear of the ag department’s classroom and shop. Solving problems along the way is a big part of any business, of course, and one of the major accomplishments of the program was moving out of those early makeshift quarters. Through community outreach and the resulting generous donations from local organizations and residents, the program was able to raise the money to construct a dedicated, tailored space. The Dr. Bill McDonald Animal Science Pavilion memorializes an Orange County veterinarian, school board member and longtime supporter of local youth. McDonald passed away in January 2018 at age 47 after suffering severe burns in an accident outside his home.

The $250,000 facility was completed in July 2018 and became home to its first animals that November. It’s located beside the greenhouse, and the program worked with Orange County-based Riverview Farms to be sure the technology used inside is the same as what students would find for gestation, farrowing, nursing and grow out on a commercial hog farm. “We paid for every penny of that,” Scott reflected.

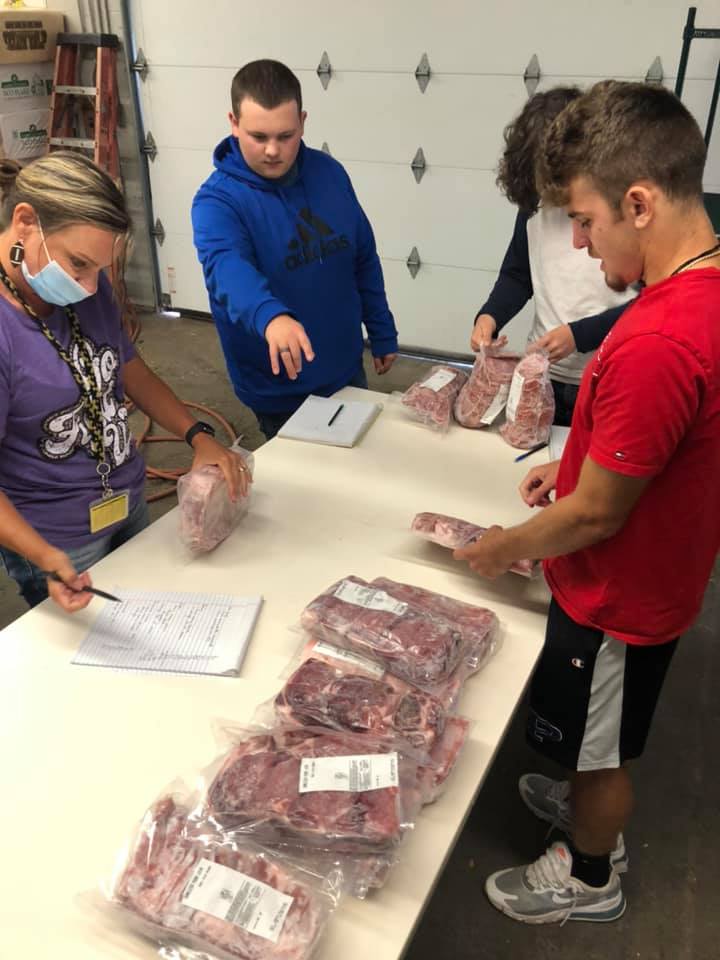

Six hogs are housed on site now, and another eight program animals are kept at students’ home farms or other properties, all on a co-op basis, in order to meet demand. Boots and animals from her lineage — through daughter Dolly, granddaughter Mabel and great-grandson Haus — have supplied the program with 2,000 to 2,500 pounds of pork each year.

Students are also responsible for researching the local market to come up with pricing that is competitive and will ensure profitably in order to sustain the program. “We’re probably able to profit somewhere between $1,500 and $1,800 a year,” Scott noted.

Input costs and the razor-thin nature of margins in the food industry have made big impressions on the budding entrepreneurs, especially now that costs of supplies and processing are running so high. “Even if they don’t go into business,” Scott shared, “at least they have an understanding of where their food comes from and why prices are the way they are.”

Some of the next challenges to be met include marketing pork products that aren’t usable by the school, including ribs; coming up with unique packaging to set the school’s products apart in the local marketplace; and getting the program’s composting operation back up and running.

The students have been creative with their approaches to both marketing issues, Scott said. One idea they’ve come up with for the ribs is holding tailgate parties at home football games. For the packaging, the students have been working on the design and manufacturing processes with Andrew Woodard of the Uplands Maker Mobile — a collaborative effort of the Indiana University Center for Rural Engagement, Regional Opportunity Initiatives and Radius Indiana.

The composter, meanwhile, had been extremely successful before a mechanical issue sidelined everything. A remedy is now being explored that will allow it to go back online and again turn animal waste, along with cafeteria refuse, from an expense on the income statement to saleable fertilizer for the community’s gardeners.

Vegetable production on the grow

The freed-up greenhouse space is also allowing the students to expand their produce program beyond the lettuce they’ve grown for the last several years. Cucumbers, peppers and tomatoes are just a few of the offerings now being explored. “We’ll have the capability to do whatever the kids want,” Scott said.

Since the beginning, the lettuce has been grown in the shop area, thanks to hydroponics systems the students built themselves. From beds on the floor, students increased production with the Ark: a multi-level bed operation that utilizes a pump to get water and nutrients to the uppermost beds. From there, the liquid flows down to lower beds by gravity before being pumped back to the top again.

The vertical architecture was another problem-solving measure the students came up with to meet an explosion in demand while operating within space constraints. Scott explained the original beds on the floor had been projected to be enough, based on the cafeteria’s existing lettuce consumption. However, he laughed, demand skyrocketed once diners got a taste for lettuce that actually has flavor.

An unexpected lesson in government

In 2020, the problem solving was taken to an entirely new level when the program ran up against an unforeseen hurdle that ultimately required government intervention. The school learned from the state that it couldn’t legally buy food products that weren’t at the lowest price available on the market. Scott said it simply isn’t possible for a small school-run enterprise to match the pricing of giant companies. So, the program enlisted the help of Rep. Steve Davisson, R-Salem, to find a solution at the Statehouse. “The kids worked hard and lobbied,” Scott said.

The end result was House Enrolled Act 1119, which passed the Indiana House and Indiana Senate in the 2021 legislative session and was subsequently signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb, allowing schools to purchase up to $7,500 of food per fiscal year from a youth agricultural education program.

“It has solved a problem statewide,” Davisson told Southern Indiana Business Report, “as I’ve had several schools that have started to do similar things that Paoli is doing. The students have been very supportive, and the bill had unanimous support in the legislature. Most legislators thought it was a great opportunity for students to learn and provide the food that they and their fellow students would be served in the cafeteria.”

Success brings notoriety, inside and outside PHS

Scott said the word-of-mouth advertising from students excited about what the ag program is doing has helped spur more and more interest. Within the school, it’s meaning more hands to help with work. For one thing, it has provided a deep bench of volunteers to staff the four daily one-hour shifts it takes to oversee animals outside school days.

More importantly, though, increased interest is allowing the ag program to do bigger and better things. For example, Scott said the veterinary careers class that launched last year and saw three students earn certification as veterinary assistants is on track to certify eight students this school year.

The program is also getting plenty of notice by ag publications and other schools. Calls, emails, visits and articles are helping carry the seed of Paoli’s success story to blossom in fertile fields at other Indiana schools. “It’s a real-world model that I’m just really proud of, honestly,” Scott shared.